We need to be clear why we are fixated, for the moment, on Trump. There is actually some optimism in the business community and among financial analysts about the Trump regime and what it can deliver, optimism if you are sold on neoliberal policies of deregulation and privatisation and a strong state. If Michael Wolff’s insider book Fire and Fury is to be believed, much of the policy agenda is actually being driven by ‘Jarvanka’, that is Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, Democrats who have the aim of installing Ivanka in the White House in the future (Wolff, 2018). Within the frame of this political-economic agenda, and a record of military intervention abroad, there is little evidence that Hillary Clinton would have been much more progressive in charge of the White House. The Trump vote should be set in the context of suspicion of elite machine politics that Hillary was into up to her neck and popular reaction to that, populist reaction peppered with a good dose of misogyny. In this regime, the figure of Trump himself stands out as an exception, an unpredictable element in a political movement which, as Steve Bannon feared, would be drawn into the establishment. Trump could become a generally conformist and typical member of the President’s Club. Trump is an anomaly, object of derision in the press, but should our response be in line with that derision?

The Trump election campaign was a media campaign. More than previous elections, which have been thoroughly mediatised in recent years as part of the society of the spectacle, this campaign revolved around mass media (Debord, 1967/1977). It was a campaign oriented to the media, by media and for the media. And we learn from Michael Wolff’s book that the Trump team had the media in its sights as the main prize, as the end rather than the mere means. Members of the Trump team had their eyes set on media positions at the end of a campaign they expected and hoped to lose, and Trump himself aimed to use the campaign to set up a media empire to rival Fox. They had in mind the advice by ex-Murdoch anchor-man Roger Ailes, that if you want a career in television, ‘first run for president’. The election campaign effectively continues after Trump has been installed with a proliferation of fake news and the signifier ‘fake news’ which haunts the media now. From this flows the kind of analyses we need, either analysis that will be really critical of Trump, or the kind of analysis that will easily and pretty immediately be recuperated, neutralised and absorbed by the spectacle.

It wasn’t just any old media that was crucial here, but new social media. Rapid decline in newspaper readership, which spells a crisis for the old media empires like Murdoch’s Fox News, and near-death for standard format news television programmes as a source of information, has seen a correlative rise in importance of platforms like Facebook, and, more so, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr and 4chan. These are platforms for the circulation of particular kinds of information; information that works by way of what it says and, crucially, how it is packaged. These are little packets of semiotic stuff that hook and take, they are memes. Memes as tagged images or repetitive gif files provide messages which are intimately and peculiarly bound up with the form of the media. More than ever, perhaps even now with a qualitative shift in the speed and intensity of media experience and its impact on subjectivity, the medium is the message (McLuhan, 1964). These are the memes produced and consumed in a significant component domain of contemporary politics, activating and replicating a certain mode of experiential engagement with Trump. There is something essential to be grasped here about the form of memes that keys into new forms of subjectivity and political engagement.

Take the example of the Trump open-book law-signing meme. In this gif, the big book Trump shows to camera as public evidence that a new statute has just been signed by him is inscribed with other messages; one of the earliest instances has the word ‘Kat’ and an arrow on the verso page pointing to a scrawled child-like image of cat recto (joke: Trump is childish); a later version after the exchanges with North Korea has an image of a little red scribble marked ‘his button’ on one page and a bigger splodge on the other page marked ‘my button’ (joke: Trump is childishly preoccupied with having something bigger than Kim Jong-un). The message content for this meme can be easily pasted in and posted by anyone using a mobile app that is advertised on the internet; the advertising also pokes fun at alt-rightists who might be grammatically-challenged but even so will find it simple to use (Salamy, 2017). There are elements to these gifs that are also very easy for pop-Lacanians to describe; of a Symbolic register in which the message also connotes Trump’s childish nature, of an Imaginary aspect which hooks us and replicates something childish about the intervention, and even a hint of something Real, of the stupidity of Trump as dangerous, this image-game inciting the very jouissance, the very deathly pleasure it pretends to ward off. It is as if, and only as if, we can connect with what we know about Trump, and find a way to tell the truth about him, about how we feel about him.

Take another example, Pepe the frog. This character was claimed and used by the alt-right to ventriloquise a series of often racist messages to support Trump during the election campaign. Pepe says the unthinkable, enunciates what is already said among the alt-right community. This is beyond dog-whistling politics; it includes humorous jpegs of Pepe with a Hitler moustache saying ‘Kill Jews Man’. The Anti-Defamation League is onto this, but that isn’t a problem for the alt-right; that merely heightens the peculiar pleasure of fans of Pepe. Here, you could say that an obscene underside of political discourse is relayed which pretends to connect with the unconscious, an unconscious realm which is configured as the repressed realm of what people really think and want to say. If there are perversions of the Imaginary, Symbolic and Real here, it is as if they are already conceptualised and mobilised as part of the stuff of the meme; with the performative aim to feed a relay between Imaginary and Symbolic and make the Real speak. It is as if, and only as if, the unconscious can speak, with the construction of truths that have been censored now released, finally free.

Notice that there is a particular kind of framing and localisation of the enemy and resistance. This framing and localisation brings to the fore the Angela Nagle thesis, the argument in her book Kill all Normies (Nagle, 2017) that the Left prepared the ground for the rise of the alt-right; that arrogant attempts to enclose new media platforms and shut down debate, to humiliate and ‘no-platform’ political opponents, set the conditions for an alt-right that was then much more adept at scapegoating others in order to triumph. The Nagle thesis also raises a question about the complicity of what we like to call ‘analysis’ or even ‘intervention’ when we are being more grandiose, about our complicity with the phenomena our critique keys into. We can see the looping of this critique and phenomenon in the widely-circulated little video clip of alt-right leader Richard Spencer beginning to explain what his badge with an image of Pepe the frog on it means, explaining before being punched in the face; the video becomes an Antifa gif, it becomes a meme. In the process, opponents and supporters of Trump become mediatised, part of the same looping process of memesis. So, a fantasy about what censorship is and how to break it, and what ‘free association’ is and how to enjoy it becomes part of the media in which that fantasy is represented.

Trump is seductive, and so is psychoanalytic critique of him. It is tempting to home in on Trump as a pathological personality. Perhaps he is, as Michael Wolff says, ‘unmediated’, ‘crazylike’, without what neuroscientists call ‘executive functions’, perhaps he is only mediated by his own image. This is where Wolff’s spoof anecdote, which is unfortunately not included in Fire and Fury, is so enjoyable; the one about Trump watching a special cable channel devoted to gorillas fighting, his face four inches from the screen as he gives advice to them saying things like ‘you hit him good there’. But we don’t necessarily avoid wild analysis when we simply shift focus away from Trump himself and pretend instead that psychoanalysis can explain how someone like Trump could be elected; that is the argument in Robert Samuels’ book Psychoanalyzing the Left and Right after Donald Trump (Samuels, 2016), an argument that is actually underpinned by Lacanian theory, a very accessible clear book. There is a place for psychoanalysis, but the question is, what is that place, how does psychoanalysis key into the media phenomena it wants to explain? We need to take care, take care not to be hooked by that question. We should not extrapolate from the psychoanalytic clinic to psychoanalyse politics.

Trump is a paradoxical figure, not a psychoanalytic subject but a psychoanalytic object. He cannot not be aware of psychoanalytic discourse swilling around him and framing him, so pervasive and sometimes explicit is that discourse, but he seems resistant to that discourse, showing some awareness of it even as he rails against it. This use of psychoanalytic-style critique is one of the axes of the class hatred that underlies much of the mainstream media contempt of Trump and the representations of his stupidity. It is then also one of the sub-texts of populist reaction against the media, the media seen as part of the elite that patronises those who know a little but not a lot, here those who know a little but not a lot about psychoanalysis, who know what is being pointed at but who cannot articulate what exactly is being mocked in Trump and why. He is reduced to being an object of scorn, seemingly unable to reflexively engage with psychoanalytic mockery of him as if he was an analysand, to reflexively engage as an analysand would do. It is as if we have the inverse of the anecdote reported in the Michael Wolff book in which a model asks Trump what this ‘white trash’ is that people are talking about; Trump replies ‘they are people like me, but poor’. In this case the question might be ‘What are these psychoanalytic subjects, analysands?’; Trump’s answer would be ‘they are people like me, but reflexive’. He is in this language game but not of it, and the joke is that he doesn’t quite get the joke, our sophisticated psychoanalytic joke. Trump is what Freud (1905) would term the butt of the joke, and here the butt of psychoanalytic discourse as a class weapon used against him.

Take, for example, a Trump meme which frames him as what we might call the case of Little Hands. This meme picks up on a comment twenty years ago by a journalist – it was Graydon Carter in Spy magazine – that Trump has unusually short fingers. Trump reacted badly to this comment apparently, and ever since has been mailing the journalist cut-out magazine images of Trump himself with his hands circled in pen and the scribble ‘not so short!’ During the 2016 Republican Primary one of Trump’s rivals Marco Rubio said that Trump’s hands were tiny, and ‘you know what they say about guys with tiny hands’ – he waits for laughter – ‘you can’t trust them’. Trump’s angry response took the implicit reference to the size of his dick seriously, and he responded publically in a speech in which he said ‘I guarantee you, there’s no problem’. This is where the meme poking fun at Trump spins into psychoanalytic discourse. Stories circulated in the media about this, including about the formation of a political action committee, that is an electoral campaign group, called ‘Americans Against Insecure Billionaires With Tiny Hands’. You see how this works as a double-joke; Trump is insecure about power, but he doesn’t realise that it’s about power. You could say that the meme joke revolves around the fact that he doesn’t get the difference between the penis and the phallus. The Trump Little Hands meme drums home a message about what he knows but doesn’t want to know.

So what can psychoanalytic theory as such say about this process? We need to ask why it is so easy to make a psychoanalytic argument about these political phenomena. It does indeed look as if a Kleinian account of splitting and projective identification is perfectly suited to explaining not only why Trump acts the way he does, but also, better, it explains how we become bewitched by Trump, filling him with our hopes or hatred. It looks as if a version of US-American object relations theory perfectly captures the nature of Trump as a narcissist or, better, as an expression of an age of narcissism in which we stage our political objections to him as for a meritocratic ego ideal that we want to be loved by. It looks as if Lacanian psychoanalysis identifies a cause that drives and pulls Trump through the blind alleys of desire for he knows not what and, better still, this psychoanalysis explains what it is about Trump as objet petit a that is coming close to us and causing us anxiety. These are lines of argument rehearsed by Robert Samuels. The reason why these explanations make sense is not because they are true but because they are made true, woven into the stuff they are applied to (Parker, 1997). So, there is a deeper problem in the supposed ‘application’ of psychoanalysis to politics, but is there a way out of this?

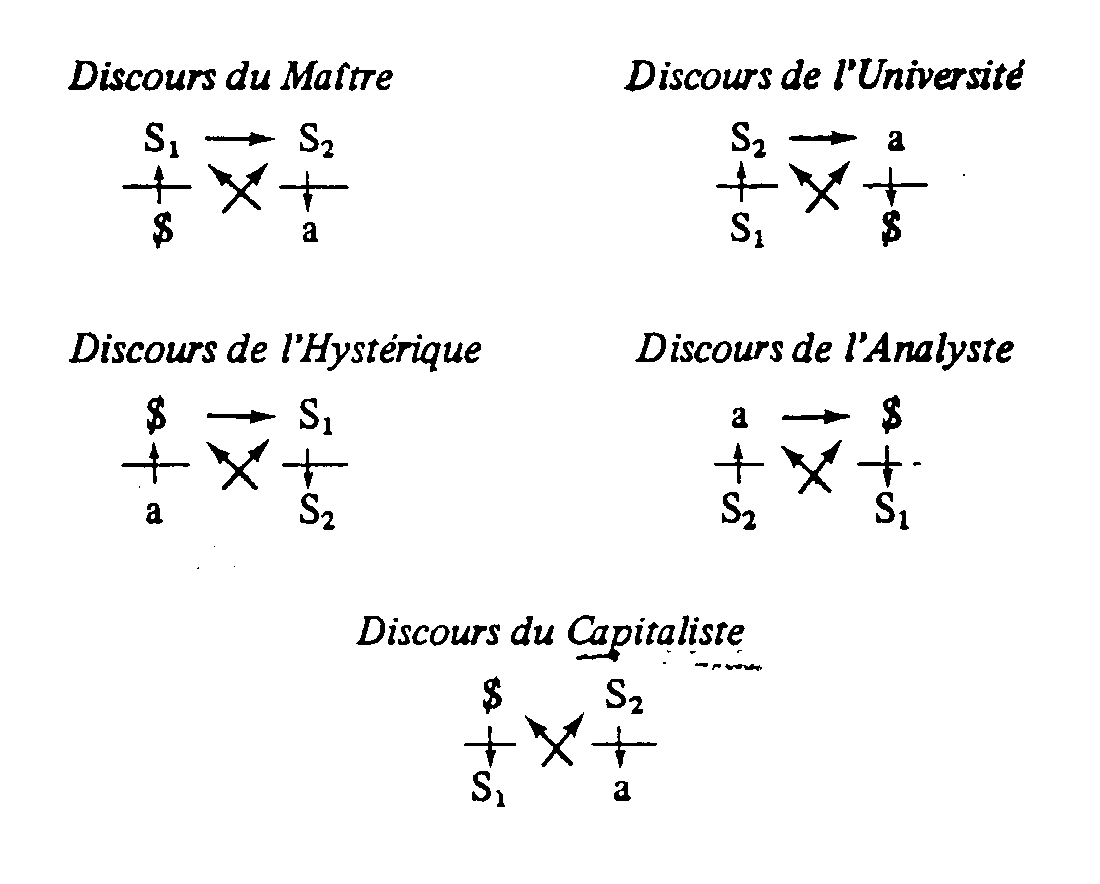

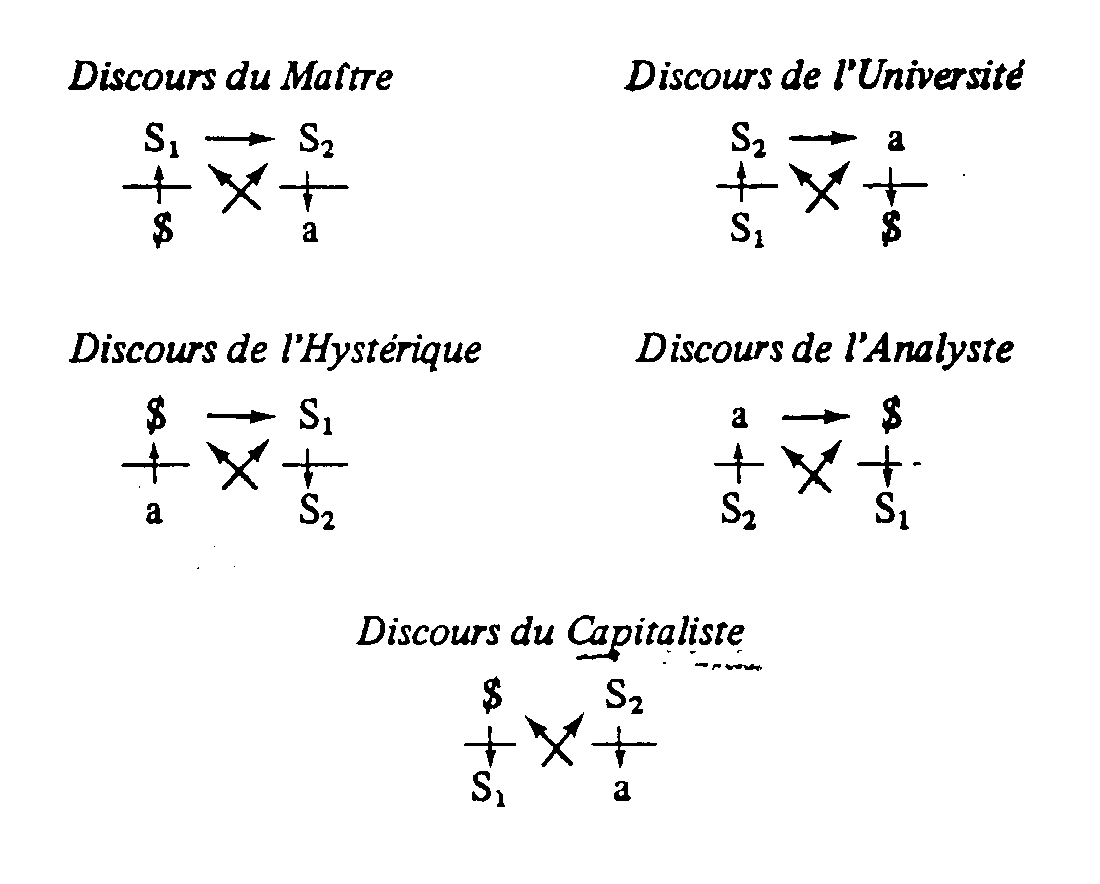

One of the peculiar things about Lacanian psychoanalysis is that it is implicitly, potentially reflexively self-critical. One of Lacan’s conceptual devices helps us to understand a bit better exactly how recuperation operates under new mediatised conditions of possibility for political discourse. I have in mind the so-called ‘discourse of the capitalist’ (Fig. 1), though I am not sure that it is actually a fifth discourse that runs alongside the other four discourses that Lacan describes (Tomšič, 2015). In Seminar XVII Lacan (1991/2007) describes four discourses in one of his few extensions of psychoanalysis beyond the clinic, to understanding the political-economic context for the psychoanalytic clinic. These discourses are, discourse of the master as foundational, foundational condition of consciousness; discourse of the university, bureaucratically pretending to include all knowledge; discourse of the hysteric, productively rebellious questioning; and discourse of the analyst, hystericizing, facilitating critique. The so-called discourse of the capitalist that Lacan (1972) briefly proposes is a twist on the discourse of the master in conditions of commodity production and, I would say, of its mutation into the society of the spectacle. Here in this discourse, the barred subject is in the position of the agent, as if we are in the discourse of the hysteric, but it faces knowledge, the battery of signifiers as other. Underneath the barred subject in the position of truth is S1, master signifier, facing the objet petit a, product (Vanheule, 2016). The master signifier is where it would be in the discourse of the university, but the end-point of this is still a commodity, as it would be in the discourse of the master. So, the discourse of the capitalist is a diagnostic tool complicit in power.

One of the peculiar things about Lacanian psychoanalysis is that it is implicitly, potentially reflexively self-critical. One of Lacan’s conceptual devices helps us to understand a bit better exactly how recuperation operates under new mediatised conditions of possibility for political discourse. I have in mind the so-called ‘discourse of the capitalist’ (Fig. 1), though I am not sure that it is actually a fifth discourse that runs alongside the other four discourses that Lacan describes (Tomšič, 2015). In Seminar XVII Lacan (1991/2007) describes four discourses in one of his few extensions of psychoanalysis beyond the clinic, to understanding the political-economic context for the psychoanalytic clinic. These discourses are, discourse of the master as foundational, foundational condition of consciousness; discourse of the university, bureaucratically pretending to include all knowledge; discourse of the hysteric, productively rebellious questioning; and discourse of the analyst, hystericizing, facilitating critique. The so-called discourse of the capitalist that Lacan (1972) briefly proposes is a twist on the discourse of the master in conditions of commodity production and, I would say, of its mutation into the society of the spectacle. Here in this discourse, the barred subject is in the position of the agent, as if we are in the discourse of the hysteric, but it faces knowledge, the battery of signifiers as other. Underneath the barred subject in the position of truth is S1, master signifier, facing the objet petit a, product (Vanheule, 2016). The master signifier is where it would be in the discourse of the university, but the end-point of this is still a commodity, as it would be in the discourse of the master. So, the discourse of the capitalist is a diagnostic tool complicit in power.

We could re-label this fifth discourse ‘the discourse of psychoanalysis’, as Lacan himself implies it is. This is not the discourse of the analyst; no element is in the same position that we find in this mutation of discourse and the discourse of the analyst, but there is some significant mapping of elements with positions in the other three discourses, especially, of course, with the foundational discourse of the master. Here it is as if the agent, hysterical barred subject, is rebellious, questioning, but this agent attacks not the master but knowledge as such, rails against all knowledge, treating it as fake news. This agent revels in their division, aware of the existence of something of the unconscious in them, loving it; they are psychoanalytic subjects, ripe for analysis, up for it. It is as if the truth of this subject will be found in the little significant scraps of master signifier that anchor it, signifying substance that seems to explain but actually explains nothing. This is how memes function in the imaginary production and reproduction of politics. This kind of truth includes those signifiers that are cobbled together from our own psychoanalytic knowledge, rather like the way they function in the discourse of the university, chatter about the ‘ego’ and the ‘unconscious’ and the rest of the paraphernalia. Two key elements of the discourse of the master are still in place; knowledge as a fragmented constellation of memes mined for meaning, for signs of conspiracy or, at least, something that serves well enough as explanation, including psychoanalytic explanation; and there is the product, objet petit a, something lost, something that escapes, something that drives us on to make more of it. We know well enough the paranoiac incomplete nature of the psychoanalysis that lures us in and keeps us going; here it is again (Parker, 2009). We can draw on the discourse of psychoanalysis to make sense of Trump, and, more importantly, how he is represented.

This discourse is one manifestation of an ‘age of interpretation’ that now circumscribes and feeds psychoanalysis. Remember that Freud did not discover the unconscious, Lacan insists on this; rather he invented it, and that invention which is coterminous with burgeoning capitalism in Europe functions (Parker, 2011). It functions not only in the clinic, but in society. When it flourishes, its prevalence as an interpretative frame poses questions for psychoanalytic practice. Psychoanalytic subjects love psychoanalysis, love psychoanalytic discourse, they want more of it, want to speak it in the clinic and want to hear it interpreted, want it fed. The questions they pose in the clinic demand certain kinds of answers, psychoanalytic answers. In what Jacques-Alain Miller (1999) calls the age of interpretation there is a real danger that the analyst buys into this, feeds the unconscious. The appropriate analytic response to this demand is not to ‘interpret’ but to ‘cut’ the discourse, to disrupt it by a particular kind of interpretation, intervention which includes cutting the session. This is also why psychoanalysis should not be merely ‘applied’, for it will merely feed what it is being applied to. These conditions of discourse call for different kinds of interpretative strategies.

There are implications of this for what we think is psychoanalytic critique of meme-politics. Mere description won’t cut it. Perhaps it calls for what Robert Samuels describes as an ethic of neutrality combined with an ethic of free association; that is, neutrality of the analyst which does not rest on empathic engagement, and free association which does not feed the fantasy that something must be censored in order for correct speech to emerge. I’m not sure this will work. Perhaps it requires performative description in which there is some kind of over-identification with the discourse and unravelling of its internal contradictions; that is, deliberate use of the terms used, memes turned against memes. In which case we risk falling into the trap that Angela Nagle describes, one in which we replicate the conditions in which the alt-right emerged triumphant. Perhaps what we need is direct critique grounded in other forms of discourse, not only the discourse of the analyst which might work in the clinic but merely hystericizes, usually unproductively hystericizes its audience when it is ‘applied’ outside the clinic. Other forms of discourse, from Situationist critique and feminism and Marxism are necessary to break from the discourse that keeps all this going. Lacanian theory can connect with those other kinds of discourse as I have tried to show. This kind of anti-Trump in the media critique needs also be anti-psychoanalytic.

So, how do we speak as psychoanalysts about Trump? We can attend to the way that psychoanalytic discourse is mobilised in the public realm, but we need to take care not to simply feed that discourse. We should not pretend that we can speak as psychoanalysts. In fact, to speak as a psychoanalyst in the clinic is itself a performative impossibility. Lacan points out that what we say in the clinic may sometimes position us as psychoanalyst for the analysand, position us as subject supposed to know, but there is no guarantee that we are speaking there to them as a psychoanalyst. To pretend to speak from the identity of psychoanalyst is to speak as if we are a subject who does know. And so, then, to speak as if we are a psychoanalyst with a privileged position to interpret political phenomena in the public realm is to perform a double-betrayal of psychoanalysis itself. Words are weapons, Trump knows that. Psychoanalysis is a double-edged weapon, and so we need to take care over how to use it to speak about politics, including how we speak about Trump.

References

Debord, G. (1967/1977) Society of the Spectacle. Detroit: Black and Red.

Freud, S. (1905) ‘Jokes and their relation to the unconscious’, in J. Strachey (ed.) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 8, London: Vintage, The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Lacan, J. (1991/2007) The Other Side of Psychoanalysis: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XVII (translated by R. Grigg). New York: Norton.

Lacan, J. (1972) ‘On psychoanalytic discourse’, http://www.lacanianworks.net/?p=334

McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw Hill.

Miller, J.-A. (1999) ‘Interpretation in reverse’, Psychoanalytical Notebooks of the London Circle, 2, 9-18.

Nagle, A. (2017) Kill all Normies: Online culture wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the alt-right. Winchester and Washington: Zero Books.

Parker, I. (1997) Psychoanalytic Culture: Psychoanalytic Discourse in Western Society. London and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Parker, I. (2009) Psychoanalytic Mythologies. London: Anthem Books.

Parker, I. (2011) Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Revolutions in Subjectivity. London and New York: Routledge.

Salamy, E. (2017) ‘Create your own Trump-signed executive order with online generator’, Newsday, 5 February (accessed 29 February 2018), https://www.newsday.com/news/nation/create-your-own-trump-signed-executive-order-with-online-generator-1.13066643

Samuels, R. (2016) Psychoanalyzing the Left and Right after Donald Trump: Conservativism, Liberalism, and Neoliberal Populisms. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tomšič, S. (2015) The Capitalist Unconscious: Marx and Lacan. London: Verso.

Vanheule, S. (2016) ‘Capitalist Discourse, Subjectivity and Lacanian Psychoanalysis’, Frontiers in Psychology, 7, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5145885/

Wolff, M. (2018) Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House. New York: Henry Holt.

This paper was published as a chapter as Parker, I. (2019) ‘Memesis and Psychoanalysis: Mediatising Trump’ in A. Bown and D. Bristow (eds) Post-Memes: Seizing the Memes of Production. Goleta, CA: Punctum Books, pp. 351-364. [ISBN-13: 978-1-950192-23-6] [doi: 10.21983/P3.0255.1.17] You can download the whole book at this link: https://punctumbooks.com/titles/post-memes-seizing-the-memes-of-production/

This is one part of the FIIMG project to put psychopolitics on the agenda for liberation movements

One of the peculiar things about Lacanian psychoanalysis is that it is implicitly, potentially reflexively self-critical. One of Lacan’s conceptual devices helps us to understand a bit better exactly how recuperation operates under new mediatised conditions of possibility for political discourse. I have in mind the so-called ‘discourse of the capitalist’ (Fig. 1), though I am not sure that it is actually a fifth discourse that runs alongside the other four discourses that Lacan describes (Tomšič, 2015). In Seminar XVII Lacan (1991/2007) describes four discourses in one of his few extensions of psychoanalysis beyond the clinic, to understanding the political-economic context for the psychoanalytic clinic. These discourses are, discourse of the master as foundational, foundational condition of consciousness; discourse of the university, bureaucratically pretending to include all knowledge; discourse of the hysteric, productively rebellious questioning; and discourse of the analyst, hystericizing, facilitating critique. The so-called discourse of the capitalist that Lacan (1972) briefly proposes is a twist on the discourse of the master in conditions of commodity production and, I would say, of its mutation into the society of the spectacle. Here in this discourse, the barred subject is in the position of the agent, as if we are in the discourse of the hysteric, but it faces knowledge, the battery of signifiers as other. Underneath the barred subject in the position of truth is S1, master signifier, facing the objet petit a, product (Vanheule, 2016). The master signifier is where it would be in the discourse of the university, but the end-point of this is still a commodity, as it would be in the discourse of the master. So, the discourse of the capitalist is a diagnostic tool complicit in power.

One of the peculiar things about Lacanian psychoanalysis is that it is implicitly, potentially reflexively self-critical. One of Lacan’s conceptual devices helps us to understand a bit better exactly how recuperation operates under new mediatised conditions of possibility for political discourse. I have in mind the so-called ‘discourse of the capitalist’ (Fig. 1), though I am not sure that it is actually a fifth discourse that runs alongside the other four discourses that Lacan describes (Tomšič, 2015). In Seminar XVII Lacan (1991/2007) describes four discourses in one of his few extensions of psychoanalysis beyond the clinic, to understanding the political-economic context for the psychoanalytic clinic. These discourses are, discourse of the master as foundational, foundational condition of consciousness; discourse of the university, bureaucratically pretending to include all knowledge; discourse of the hysteric, productively rebellious questioning; and discourse of the analyst, hystericizing, facilitating critique. The so-called discourse of the capitalist that Lacan (1972) briefly proposes is a twist on the discourse of the master in conditions of commodity production and, I would say, of its mutation into the society of the spectacle. Here in this discourse, the barred subject is in the position of the agent, as if we are in the discourse of the hysteric, but it faces knowledge, the battery of signifiers as other. Underneath the barred subject in the position of truth is S1, master signifier, facing the objet petit a, product (Vanheule, 2016). The master signifier is where it would be in the discourse of the university, but the end-point of this is still a commodity, as it would be in the discourse of the master. So, the discourse of the capitalist is a diagnostic tool complicit in power.